The Missing Diamond in AI-Generated Design

• Design, AI

If your team uses AI for design, you already know the upside: you can go from rough idea to polished UI in hours, not days. That shift is real, and it changes how teams work day to day.

The problem is what speed can hide. Polished screens start to look like validated thinking, even when the user problem is still fuzzy. Teams commit to build plans too early, then learn from adoption and support data what discovery should have caught before implementation. This post looks at why that happens, what "the missing diamond" means in practice, and how to keep the speed without paying for rework later.

How Teams Go From Rough Idea to Polished UI

The new workflow is straightforward. A team starts with a problem statement, feature concept, or rough flow, then prompts AI tools to generate multiple interface directions. They refine by constraint: tone, layout density, interaction style, component library fit, accessibility targets, and platform context. In one or two sessions, they can produce several viable screens, tighten copy, and create a clickable prototype for review. This used to take far longer and usually required more handoff cycles. The speed is a genuine advantage because it lets teams discuss concrete options early instead of debating abstractions.

Used well, this shifts effort into exploration. Teams can test several directions in parallel, kill weak ideas quickly, and improve the quality of design decisions before implementation begins. It also helps cross-functional alignment because product, design, and engineering can react to the same artifact instead of talking past each other. In that sense, AI is excellent for ideation and rapid iteration.

The Downside If You Use Speed the Wrong Way

Speed is useful, but the outcome depends on how teams use the time they get back. Some teams reinvest it into broader exploration, sharper testing, and better evidence. Others use it to accelerate build commitments. Polished output creates a false sense of certainty. As visual quality climbs, it becomes easier to treat "looks good" as "is correct," and that is usually when the sequence starts to drift.

Teams move from prompt to prototype, then to roadmap and estimates, before they validate whether the proposed design actually supports the user goal. Once timelines and architecture decisions lock, the organization becomes resistant to course correction, and even good objections get treated as delivery risk instead of quality control.

What User Problem Are We Solving?

This is the core question many teams skip when prototypes look polished. Product design is not an art contest, and it is not about polishing components for their own sake. It exists to help users complete important tasks with less friction, better confidence, and better outcomes. A feature should have a clear job: reduce time, reduce error, improve decision quality, increase completion, or unlock something users could not do before.

Design is the layer that makes the product’s value usable. If the product strategy says "help users do X," the design must make X obvious, fast, and trustworthy in the user’s actual context. For example, a dashboard generated by AI might look clean and balanced. But if the user’s real job is to detect anomalies quickly under time pressure, the design must optimize for scanning speed, not aesthetic harmony. That means the design work is never separate from problem framing. A beautiful interface that adds cognitive noise, hides key actions, or disrupts task flow is still bad design, even if it demos well.

What Adoption and Support Data Catch Later

When discovery is weak, production data usually exposes it. Adoption can mean activation rate, feature usage depth, completion rates, retention, expansion, or repeat usage depending on the product model. Support signals include ticket volume, repeated confusion themes, workaround requests, onboarding failure patterns, and documentation gaps users keep hitting. You may also see longer time-to-value, lower conversion between steps, or high abandonment at specific screens.

These signals are valuable, but they arrive late. They are showing you what early discovery and validation should have identified before implementation scaled. By the time they appear, the team is dealing with remediation under time pressure instead of building from a strong foundation.

What the Missing Diamond Means

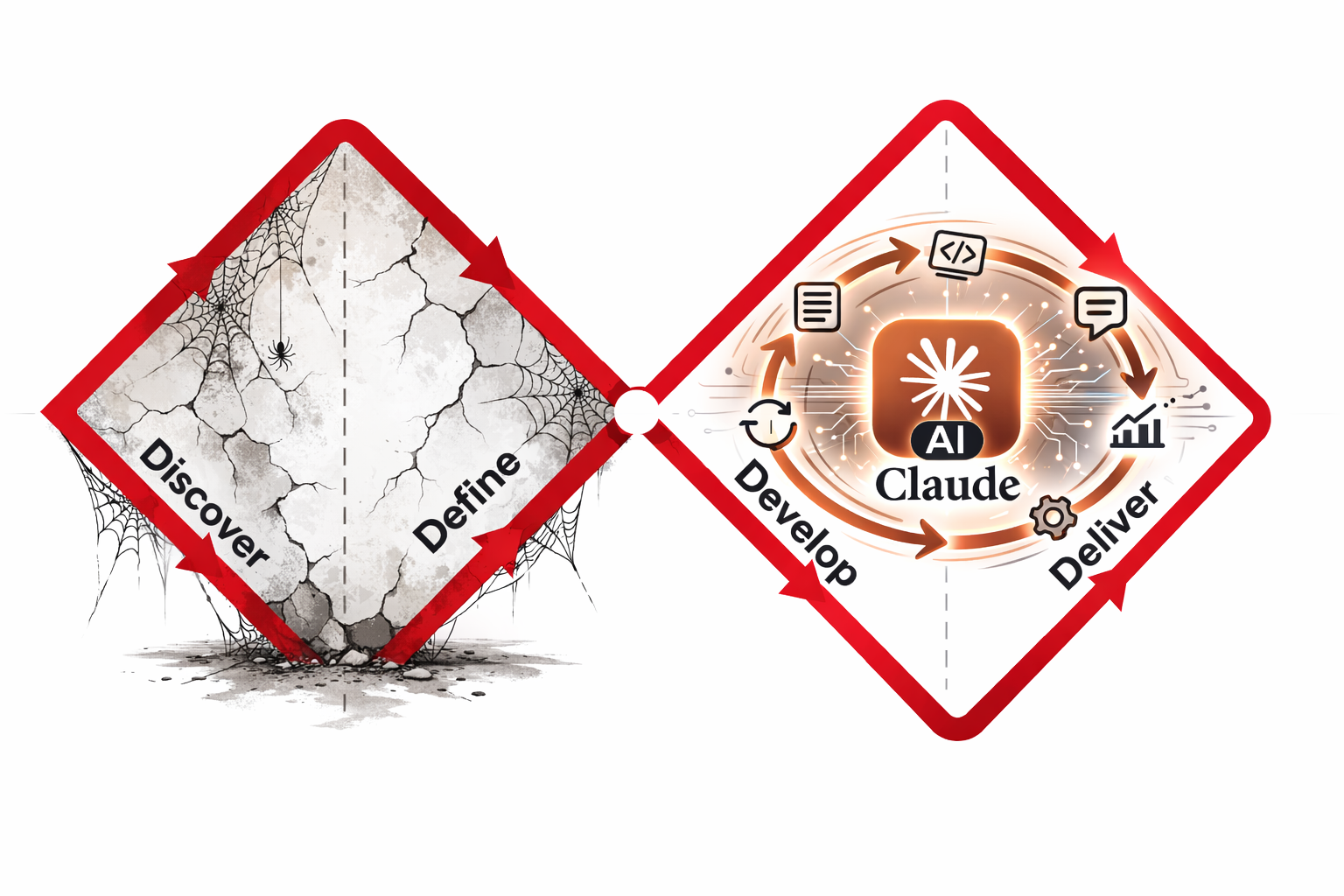

The "diamond" reference comes from the Double Diamond model. The first diamond is Discover and Define: understand users, context, and the real problem before committing. The second diamond is Develop and Deliver: create options, choose, and ship. AI is strongest in the second diamond, which is why teams feel immediate speed gains there.

The old model is not wrong because AI exists. What changed is execution speed. The faster the second diamond gets, the easier it is for teams to skip or underfund the first one. So the "missing diamond" is not a theory problem. It is an operating problem: teams preserve output velocity but lose problem clarity.

Best Path Forward

Start before the first design prompt. Write three short lines the team agrees on: what the user needs to do, what gets in the way today, and what should improve if the design works. For example: user needs to find unusual spending quickly; right now they have to click through too many screens; success means they can spot issues in one view. This is less about wording and more about alignment. If the team cannot write these lines clearly, the problem definition is still weak. Doing this first keeps design work tied to user outcomes instead of internal preferences.

Next, require one measurable job to be done before anyone judges aesthetics. Define what success means in behavior terms: complete this task in under two minutes, reduce errors on this step, increase completion from this screen. Now the design review has a real standard. You are no longer asking, “Do we like this?” You are asking, “Does this help the user complete the job better?” That shift alone removes a lot of noise from review discussions.

Use AI to explore, not to prematurely finalize. Start by generating several design directions tied to the same user job, then write the assumption each direction depends on. Ask AI for research questions that can challenge those assumptions, and use those questions in a quick internal review followed by a short check with real users in realistic conditions. Keep design exploration code in temporary branches and treat it as disposable until a direction proves itself. Once feedback is in, compare expected behavior with actual behavior, keep the strongest direction, and close the rest. This keeps discovery practical and focused, while using AI’s speed to improve decisions instead of just increasing output.